3.1

This week we go back in time to explore the legendary Monte Verità: the proto-hippie commune that would inspire the revolutions of the 60s, and the next stop on our journey through Swiss Utopias. In the autumn of 1900, a small group of young German non-conformists settled on a hill near Ascona, on the Swiss side of Lake Maggiore; two musicians, a painter with an ascetic spirit, an ex-soldier of the Habsburg army, a girl passionate about esotericism and the heir to an industrial dynasty – all dreamers and rebellious spirits seeking a new life in harmony with nature, turning their back on the social conventions of the contemporary bourgeois society. It was during this more innocent time, before the catastrophes of World War I, that they decided to create a new world: an alternative to industrialised modernity that they felt threatened both body and soul. With the riches provided by the heir, Henri Oedenkoven, they bought a few hectares of the hill, cleared the land and built huts. They let their hair grow long, practiced veganism, yoga, nudism, indulged in ‘sun baths’, ‘free love’, and a form of improvised dance that involved new steps and bodily movements that had never been seen before. Baptized as Monte Verità – ‘the hill of truth’ – it became a pilgrimage site for the leading bohemian intellectuals of the day, including Hermann Hesse, the playwright Erich Mühsam, the dancer Isadora Duncan, the dancer-choreographers Mary Wigman and Rudolf von Laban, and the sociologist Max Weber.

3.2

Although Monte Verità was aimed at reconnecting humankind with its place in nature, technology played a huge role in making this utopia a reality. The Monteveritans were surprisingly futuristic in their philosophy: embracing the most advanced technologies of the time to create a post-scarcity society. “We make judicious use of all the tools made available by science and modern hygiene”, wrote Henri Oedenkoven, one of the community’s founders, in 1903, “we lack nothing”. They had even acquired a source of water in the vicinity to produce electricity and thus get the light and energy required to run their machines. “We want everyone, without having to leave the area, to be able to have everything they want at their fingertips, without the help of servants. Given the simplicity of our way of life and with the help of modern machinery capable of producing everything, everyone will be able to provide for themselves.” This would free Monte Verità’s “followers” to focus on the personal and spiritual development required for the new world they hoped to create, and the daily rituals they would perform to achieve this. These meditation exercises, coupled with their diet, artistic play and uninhibited sexual expression would transform each of them into a model agent of this new world.

3.3

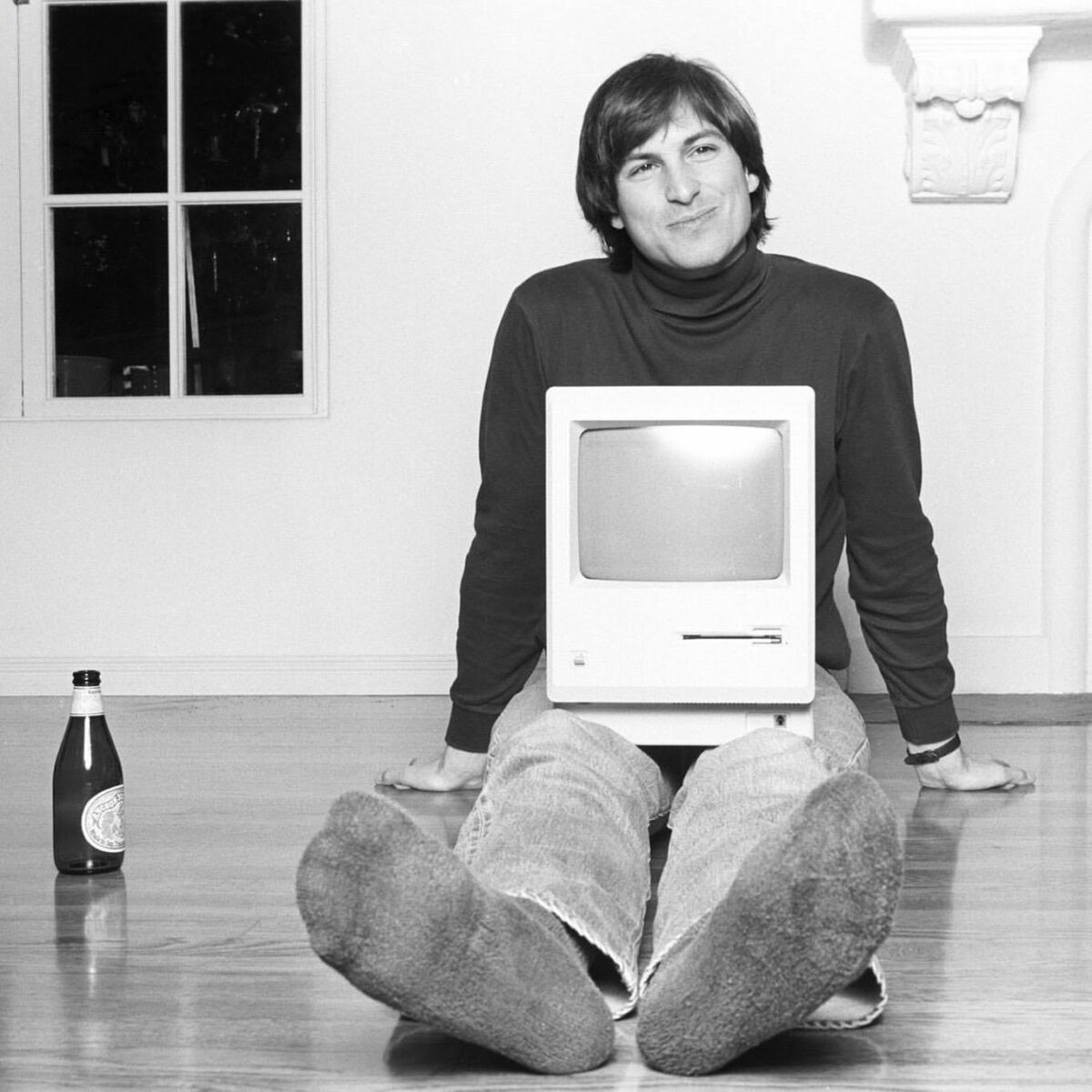

Monte Verità’s initial form may have been short-lived, marked from the beginning by the infighting that often accompanies radical movements, but its legacy remains hugely influential in countercultural movements. In many ways, the revolutionary movements of the 1960s can be traced to the shores of that lake in Switzerland: from styles of fashion to psychedelic music, meditative practices and engagement with Eastern spirituality, the sexual revolution and even the seeds of contemporary ecology. Ironically, even a global megacorp such as Apple has roots in Monte Verità. In the 1970s, Steve Jobs was such a die-hard follower of a diet largely based on the consumption of apples – developed by Arnold Ehret, one of the original inhabitants of Monte Verità – which found its way to the United States, that he decided to baptize his start-up with the name of his favourite fruit. It’s only fitting that Fondazione @monteveritaascona has in turn transformed the former colony into a diffused museum complex which houses the historic exhibition “Monte Verità. Le mammelle della verità” by Harald Szeemann, the brilliant Swiss curator and exhibition maker, who helped rescue Monte Verità from disappearing into obscurity. The impact that a tiny Alpine community, now largely forgotten, has had – and continues to have – on Western society demonstrates the role that utopian projects can play in transforming reality.